Cleanup is defined as “the act or process of removing a dirty or dangerous substance, especially when it has been left in the environment”. Is that realistic when an entire square mile is involved? The logical pathway is to pick our battles.

Natural attenuation uses naturally occurring processes to reduce contaminants in soil. Key processes include biodegradation (microbes breaking down contaminants) and abiotic degradation (chemical reactions with minerals), alongside physical processes like dilution, dispersion, and sorption (contaminants sticking to soil). It’s a passive, less intrusive remediation strategy suitable for situations where the source of contamination has been removed or is being controlled and natural processes can effectively address the remaining pollution over time. The sources may be hotspots in marine sediments or areas where polluting activities occurred on land.

Though we do our best, what’s left is still a problem. Bioaccumulation is the gradual buildup of chemicals or contaminants in a living organism where the substance is absorbed and stored faster than it can be metabolized or excreted. This process often involves fat-soluble chemicals including persistent organic pollutants (POPs), which are not easily broken down by the organism. The effects are often amplified by biomagnification, where concentrations increase at each successive trophic level of the food chain. The accumulation of these substances, especially in top predators like large fish and humans, can pose risks to health. The only solution at some level is protection from exposure through warnings and barriers.

The primary chemical of concern in Budd Inlet is dioxin, which is actually a family of chemicals with similar structures, being built around chlorine. Chlorine typically exists as a Cl₂ molecule, where two chlorine atoms are bonded but it can also exist as individual highly reactive chlorine atoms. Dioxin biodegradation primarily occurs through the enzymatic action of specialized bacteria or fungi, which break down persistent organic pollutants into less toxic compounds. Aerobic degradation involves oxidative pathways while anaerobic degradation relies on reductive dechlorination to remove chlorine atoms.

Photodegradation is the breakdown in materials caused by the absorption of light, particularly ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Photodegradation can be a comparatively quick process but can generally only occur on the surface. A substance must absorb light energy (photons). The absorbed light energy can break chemical bonds within molecules often resulting in the formation of free radicals and further chemical reactions, such as oxidation.

Biodegradation is the natural process where organic materials are broken down into simpler, harmless components by living organisms such as bacteria. Typically microorganisms release enzymes which break down complex organic molecules in the material into smaller, simpler pieces which are then consumed as a source of energy and nutrients which through metabolic processes are converted into simpler products, such as carbon dioxide, water, and new biomass. The end products are typically non-toxic and can be reabsorbed into the environment.

In a process called enzymatic dehalogenation, enzymes cleave chlorine atoms from the dioxin structure, breaking the molecule’s resistance to degradation and reducing its toxicity. Anaerobic degradation is a process wherein anaerobic bacteria remove chlorine atoms from highly chlorinated dioxins converting them into less chlorinated, more readily degradable compounds. Aerobic degradation is process wherein aerobic bacteria introduce oxygen into the dioxin molecule’s ring structure.

Bioremediation can include processes such as composting which leverages microbial activity to degrade dioxins. Bioaugmentation introduces cultured microorganisms with dioxin-degrading capabilities to a contaminated site. Biostimulation enhances the activity of naturally occurring microbial communities by providing them with optimal conditions, such as nutrients, to accelerate the degradation process. Phytoremediation utilizes plants with large biomass such as trees and strong adsorption capabilities to remove dioxins from the soil.

Restoration is defined as the act of “returning something to a former, original condition, place, or position”. Species evolve over time to live in a specific depth, salinity, acidity, temperature and other factors that evolve over thousands or millions of years based on geologic factors like flow, shape and structure, processes that are beyond our complete understanding.

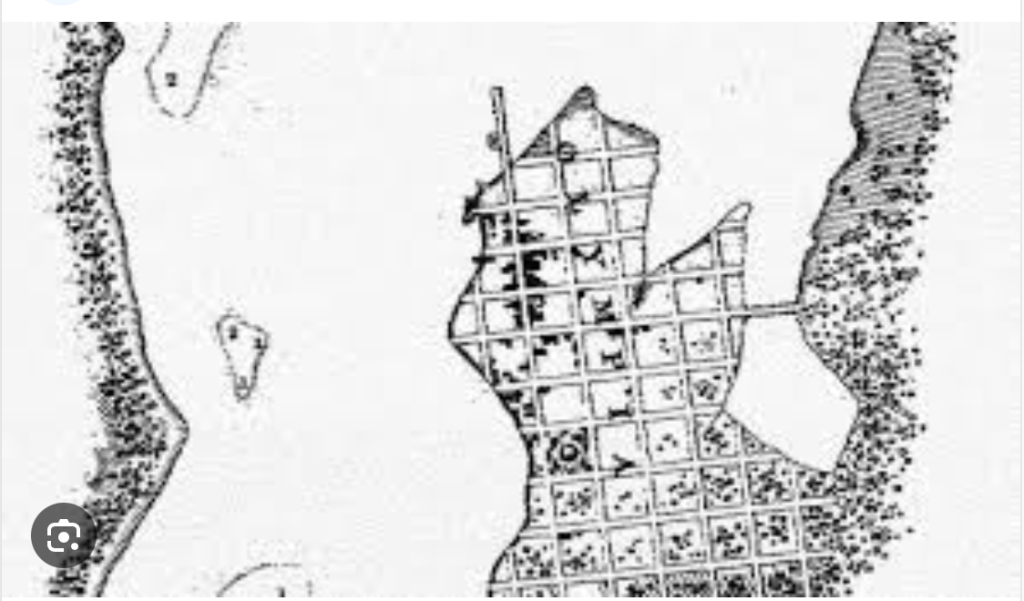

The best we can do is go back to what was before our modifications. We have maps and charts dating back to the mid 19th century and aerial photos from the mid 20th century showing what was in great detail. We can structure the shape of Budd Inlet, a finger of land here, a sand bar there, open and closed systems in all their splendor. These can guide restoration.

Altering physical parameters by such means as running a stream through a pipe can impact biological and chemical parameters; no sunlight no phytoplankton; no phytoplankton no dissolved oxygen. Moxlie Creek prior to flowing into East Bay flows through a half mile long culvert, the last section of which is owned by the Port.

Altering the structure of the bay itself can also impact dissolved oxygen. In the 1980 EIS for East Bay Marina Federal agencies initially opposed the East Bay location. In letters dated June 9, 1975 and February 26, 1980 USFWS reviewed “the subject applications to dredge entrance channels and moorage basin, fill, riprap, construct a breakwater, install floats, pier, and other facilities for a marina and cargo storage area in East Bay of Budd Inlet at Olympia, Washington” and recommended denial of project proposals because of “anticipated extensive losses of fish and wildlife”.

What was predicted in the EIS has come to pass. In many ways this is not a disadvantageous situation. There’s lots of room for improvement. Opportunities abound. What can we undo? What can we put back? Assuming that it’s unrealistic at this time to consider removing Swantown Marina we can still turn things around.

The nearshore zone is the narrow area at the interface of terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystem types that rings Puget Sound. The nearshore zone is composed of features such as beaches, embayments, and deltas that are shaped by the interaction of coastal geomorphology and local environmental conditions and provides important ecological services. Human-caused changes to the nearshore zone have impacted ecosystem function.

The Puget Sound Nearshore Ecosystem Restoration Project, was a coordinated effort by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) to evaluate “problems and potential solutions to ecosystem degradation and habitat loss in Puget Sound”. Completed in 2016, The Puget Sound Nearshore Study is a coordinated effort to create ecosystem restoration strategy based on a tiered implementation approach. Of the 36 sites identified in a feasibility study, three are recommended for immediate authorization: Duckabush River Estuary, Nooksack River Delta and North Fork Skagit River Delta. Other projects have come to the forefront since including the Deschutes River estuary.

But this is only three or four locations. More than 2,500 miles of beaches, estuaries and river deltas make up Puget Sound’s nearshore zone. 35% of historical coastal embayments have been lost. 74% of tidal wetlands surrounding the shores of Puget Sound have been lost. Many shorelines are experiencing multiple stressors and cumulative impacts. Activities are frequently planned in sensitive areas for reasons other than restoration, activities such as business and real estate development. Work must comply with rules that don’t include restoration. We theoretically can’t damage a site. We can however allow a site to remain in a damaged state.

We really shouldn’t ignore ecological potential. What values can we protect, restore and enhance? What guidelines might we follow? Even if all we care about is money, restoration can increase value. In fact increasing value is rarely a goal. Serving special interests is — the line of consultants, developers, planners of various kinds standing with their hands out.

A narrow band of shoreline serves as a transition zone providing ecologically important connections between the terrestrial, freshwater and marine ecosystem types. These beaches, embayments and delta shorelines are heavily impacted by human changes. Therefore, the nearshore zone is a strategic focus for Puget Sound recovery.

Restoration typically involves actions supporting or restoring the dynamic processes that generate and sustain desirable nearshore ecosystem structure (e.g., eelgrass beds) and functions (e.g., salmon production, bivalve production, and clean water). In most cases, this involves removing or modifying human-built structures that have interfered with essential ecosystem processes. Process-based restoration is distinguished from species-based restoration, which aims to improve habitat conditions for a single species or group of species. Nearshore Study objectives seek to benefit the entire ecosystem, with associated improvements in the delivery of broader ecosystem functions and qualities.

“The need for the proposed action comes from recognizing that valuable natural resources in Puget Sound have declined to a point that the ecosystem may no longer be self-sustaining without immediate intervention to curtail significant ecological degradation. Impairment of nearshore processes and degradation of ecosystem functions are critical factors in the declining health of Puget Sound. Anthropogenic stressors causing this impairment and degradation include the direct effects of physical alterations to the landscape that have eliminated large expanses of habitat and have disrupted the major ecological processes that create and sustain habitats. The degradation and loss of nearshore ecosystems is of critical importance because the nearshore zone serves as the connection between terrestrial, freshwater, and marine ecosystems. This means that the nearshore zone vitality, resilience, and productivity influence the productivity of the entire Puget Sound Basin. The alterations to the physiographic processes of the nearshore zone directly affect the ecosystem functions upon which humans depend such as fisheries, aquaculture, and recreation.”

And finally, Executive Order 13045 (protection of children) requires each Federal agency to “identify and assess environmental risks and safety risks [that] may disproportionately affect children” and ensure that its “policies, programs, activities, and standards address disproportionate risks to children that result from environmental health risks or safety risks.” How is expanding a Hands On Children’s Museum in the proximity of a dioxin hot spot not placing children under a disproportionate risk?

‘With 2021–2030 declared as the United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration, efforts are scaling up to reverse degradation of ecosystems worldwide, including natural and urban ecosystems. Ecosystem restoration is considered changing the nature of the human footprint within and across ecosystems rather than removing the human footprint… a continuum of restorative actions that combine human engineered and ecological solutions.

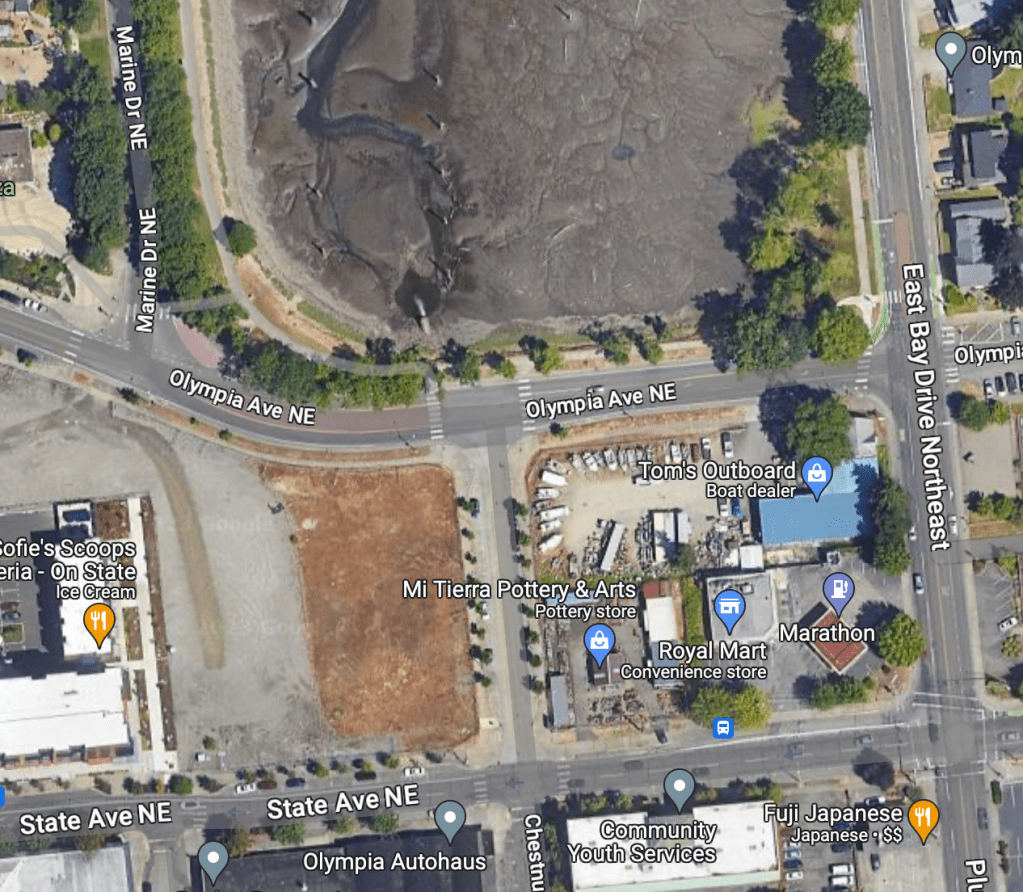

Daylight Moxlie Creek between Olympia and State Avenues. Moxlie Creek in this area is intertidal so a restoration could include tide flats and salt marsh.

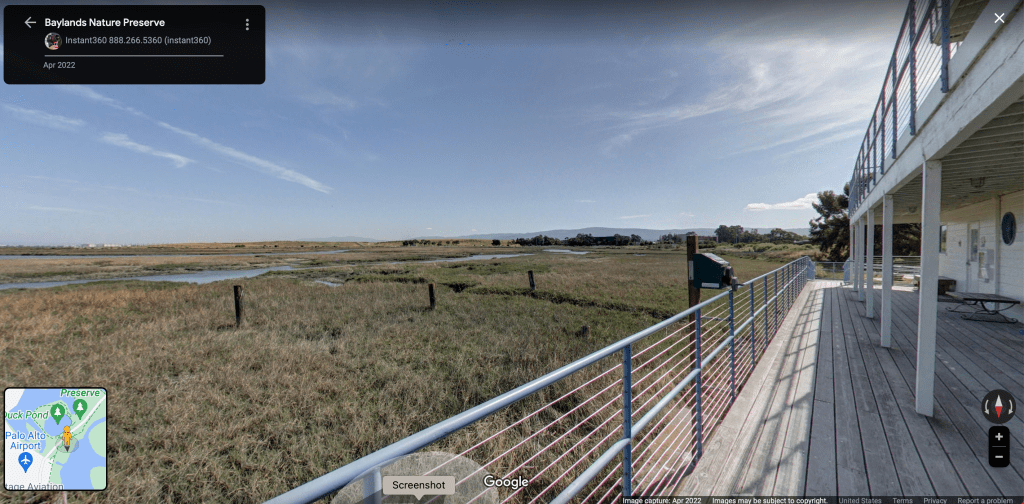

Design single structures surrounded on all sides by salt marsh. Below is a photo of what was the Palo Alto Yacht Club, the place I learned to sail many years ago. Now part of the Baylands Nature Preserve, some marina pilings are still visible.

Assess the East Bay shoreline for dioxin. Remove contamination and knock back the bank to create an upper beach. Dredge channels and benthic hot spots. Get to an acceptable ambient level with no ongoing sources so nature can begin healing.

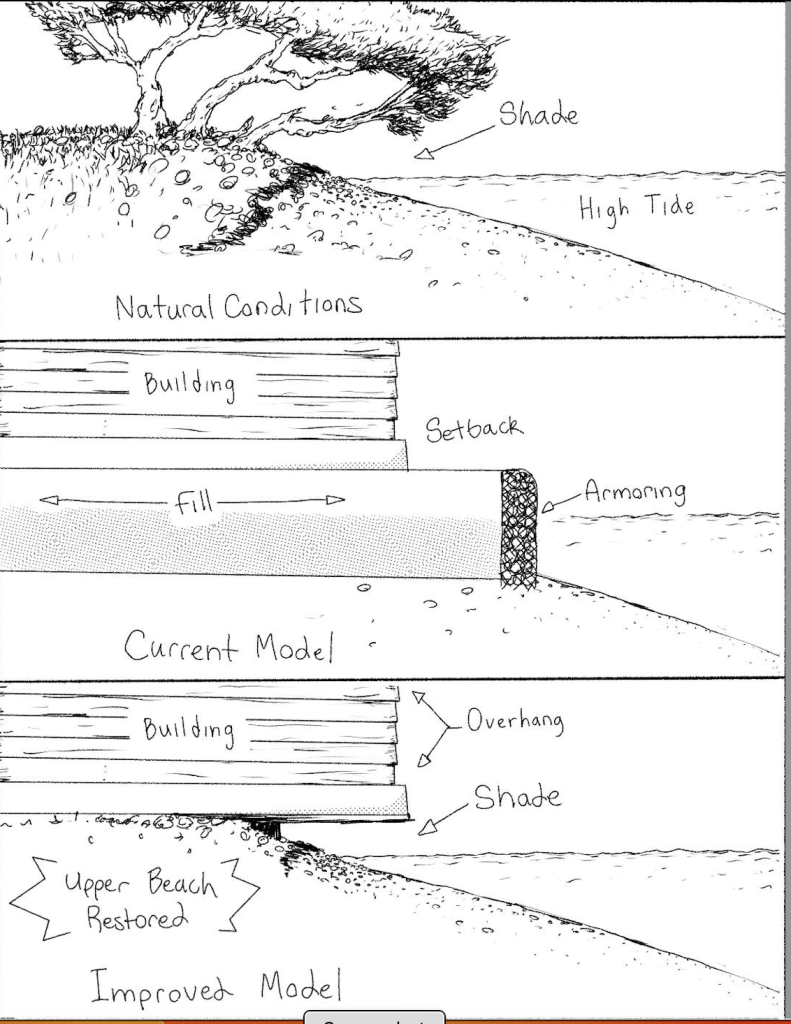

Design buildings to mimic overhanging vegetation. Natural conditions bear little resemblance to the current model and many to the improved model. Buildings in East Bay would be set back far enough from the current high water mark. That they would ultimately be overhanging the high tide mark is secondary.

There are over 100 artesian wells and springs in downtown Olympia. There are no sediments or nutrients in this water. Hence there is no sedimentation, only erosion. The map below from the mid-nineteenth century shows a pronounced wedge facing northeast from downtown in the location of a historic spring that still flows underground to this day at a rate of 60 gallons per minute. The spring was diverted to the west and its effects can be seen in photos from the 1930s in the vicinity of Percival Landing. Perhaps the scouring effects of artesian water could be utilized to maintain channels?

What’s in a name? From the book “Fort Nisqually: A Documented History of Indian and British and Interaction”” by Nisqually Tribal Historian Cecelia Svinth Carpenter: “The name Sequalitchew is said to signify or describe this projection of sandy beach at the outlet of the creek. It has been interpreted to mean ‘extensive sand banks over which the water is shallow’ and also as ‘big tide’ or ‘long run-out tide’ due to the fact that the sand was exposed for a great distance at low tide.” It could be “determined that Indian people who made their home at the mouth of the Sequalitchew Creek would then be known as the People of the Sequalitchew”.

Sequalitchew Creek lies near the mouth of the Nisqually River. There were two longhouses at the stream’s mouth housing between 40 and 50 people perhaps representing five or six extended family units. Villages of as many as 100 people were located in the estuaries of significant streams and rivers. The longhouses provided winter shelter. In summers some people moved to temporary shelters to hunt and gather plants and berries.

The Deschutes, was named Steh-chass River. The Steh-chass people lived in three large cedar plank homes, up to eight families in each. This would likely be about 100 people. Another village, Bus-chut-hwud, “frequented by black bears”, was located near what is today Percival Landing in downtown Olympia. In what is today East Bay, a long estuary lead to another village and namesake stream, the Pe’tzlb. Other pronunciations include Schict-woot or Cheet-woot which meant “place of the bear” and Stu-chus-and, Stitchas and Stechass with various meanings of “bear’s place. (1)(2)(3)(4)

The source of East Bay is Moxlie Creek which is fed by a spring a mile and a half upstream and Indian Creek which meanders farther to the East. The origin of the name Indian Creek is unknown. A safe assumption might be that a sizable Indian population resettled along the creek for some time after white settlement. There were also villages in the estuaries of Percival and Ellis Creeks and one in the estuary of Schneider Creek. (5).

Agents were expected to coax people onto the reservations but this wasn’t easy. At first many people remained on their homeland and would go to the woods to gather essentials, to the prairies in spring to dig bulbs and roots and toward the foothills in summer to pick berries and hunt for deer and elk and in the fall returning to the Nisqually to fish. These activities became increasingly difficult as land became fenced and farmed and a variety of conflicts arose. Ron Secrist whose ancestors settled in the estuary of Schneider Creek tells of Indian people who continued to live as neighbors in the lower Schneider Creek valley and estuary until a young child was killed by the Schneider’s pig. It was apparent that the two cultures could not coexist in the same locations. Americans smelled bad, they carried disease, they bred like flies, they raised pigs and they put fences around land they thought they owned.

There are things we might learn from indigenous cultures. We can learn, for example, to honor nature rather than attempting to dominate nature. The misapplication of scientific methods in is an attempt to dominate nature, an attempt that will surely fail. The phrase, often attributed to Lakota holy man Black Elk, states: “We don’t have to heal the Earth, she can heal herself. All we have to do is stop making her sick”. This wisdom suggests that the Earth possesses an inherent capacity for self-recovery if humanity ceases to cause harm and disrespect its natural rhythms. The message also implies a reciprocal relationship, where a healthier Earth can, in turn, heal and balance humanity

(1) (Meany, Origin of Washington Geographic Names, page 197.

(2) (Waterman, Puget Sound Geography, Mss.)

(3) https://www.olyblog.net/newWP/thurston-county-place-names/

(4) (Newell, Rogues, page 13.)

(5) Interview with Ron Seacrest