The Capitol Lake Debate was carried on for a number of years between two groups: The Deschutes Estuary Restoration Team (DERT) and the Capitol Lake Improvement and Protection Association (CLIPA). DERT’s argument was that the lake is an unnatural feature that impedes water quality and the dam should be removed. CLIPA’s argument was that the dam went in in 1950 and as of 1980 Budd Inlet was still a productive, resilient estuary and the problems must reside elsewhere.

In August of 2021 the state released The Capitol Lake Deschutes Estuary Long Term Management Project Draft Environmental Impact Statement. The purpose of the document is to help inform the decision whether to remove the Capitol Lake dam and return the lake to an intertidal area. It’s an impressive looking 700 plus pages with lots of graphs and data. Unfortunately a previous step was omitted. The study leans heavily toward engineering. Engineering is not science. Science tells us what we need to do. Engineering tells us how to do it.

The most relevant scientific discipline would be oceanography, the study of the interrelationships between physical, chemical and biological parameters. In oceanography, “physical parameters” refer to the measurable physical properties of seawater like temperature, salinity, density, and currents; “chemical parameters” encompass the composition of seawater, including dissolved elements like nitrate, phosphate, and dissolved oxygen; “biological parameters” relate to the living organisms present in the ocean, such as phytoplankton, zooplankton, and fish populations, along with factors like biodiversity and biomass. None of this appears anywhere in the FEIS.

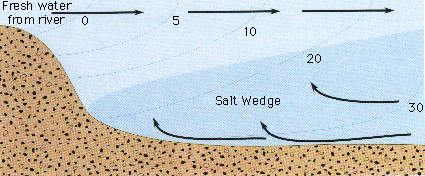

For an estuary in a bay like Budd Inlet, the FEIS is distorted because there’s no mention of the salt wedge. According to any good text book or dictionary that would be the case. From Oxford: “An intrusion of sea water into a tidal estuary in the form of a wedge along the bed of the estuary. The lighter fresh water from riverine sources overrides the denser salt water from marine sources unless mixing of the water masses is caused by estuarine topography. Salt wedges are found in estuaries where a river discharges through a relatively narrow channel.” The salt wedge is clearly visible north of Schneider Creek. East Bay and Moxlie Creek are hence vital components of the estuary. That these features are eliminated from the study area is a consequential omission.

As a result, the EIS is flawed in its scoping. The study area is defined as including what is now Capitol Lake and West Bay out to the end of the Port Peninsula because this is the area directly impacted by work. It’s what’s defined as the estuary. In estuaries, fresh water flows out on the surface of heavier salt water creating persistent mixing patterns. This “salt wedge” can frequently be observed well north of the Port Peninsula. The waters of East and West bay are part of the same estuarine system.

Also, there are repeated references to the Deschutes TMDL which was challenged in a March of 2024 civil action brought by Northwest Environmental Advocates in which NWEA ultimately prevailed. Reading the FEIS one can’t help but wonder what else is off and why.

River estuaries in Puget Sound often have a companion stream that shapes and expands the area – Hylebos for the Puyallup, Medicine Creek for the Nisqually, and Moxie Creek for the Deschutes. Moxlie Creek flows into East Bay which is a critical part of the structure of the Deschutes River estuary.

Dioxin contamination in surface sediments is an indication of uncontrolled sources. Chemical analysis informs us that this contamination is in the form of Cascade Pole wood preservatives. Cascade Pole operated on the tip of the Port Peninsula for a number of years, leaving a legacy of contamination. If we don’t identify and control sources of contamination prior to removing the dam, clean soil will enter the bay from the upper watershed to be contaminated by these sources and we’ll have a larger volume of dioxin laced mud.

The State has accumulated enough samples from the bay to have a good picture of the distribution of contamination. Several hotspots in particular have been identified. At this point we should be working to identify the nature and extent of contamination and pinpoint sources which can then be removed or controlled. These sources are likely on land since that’s where human activities generally occur. The Model has instead been flipped. We address sites in the order in which they are developed. Assuming that the assessments are adequate and done according to established protocols, an unwarranted assumption, this leaves neighboring sites unaddressed allowing for recontamination.

If we had followed methods of scientific inquiry, this EIS would read much differently. We would have a clearer idea of what scope and parameters should be included and what advantages and disadvantages are represented in each option. We can’t propose to do half the job. Cleanup must precede restoration.

East Bay versus West Bay:

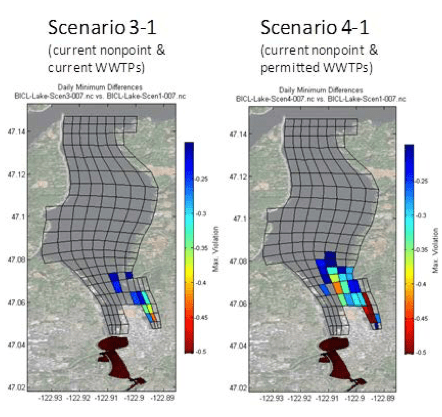

Levels of Dissolved Oxygen

Water Quality Improvement Report, 2012: https://apps.ecology.wa.gov/publications/documents/1203008.pdf

East Bay is once again the embayment on the right. Consistently East Bay has the poorest water quality for all parameters. There are low levels of dissolved oxygen and high levels of PCBs and dioxin. East Bay is a federally degraded water body. We can’t simply write it off.

In a letter dated December 05, 2015, City Manager Steve Hall writes: “Our current environmental restoration efforts in the City are focused on West Bay which has active salmon runs, bird nesting and many other advantages over the Moxlie area. We are in the middle of a habitat study on west bay with the Squaxin Island tribe, the Port and others to improve environmental conditions on West Bay. Any future dollars we invest in restoration are likely to be directed there and not to East Bay. We don’t have the staff or money to also do Moxlie and I would not recommend the City or the Port change course from our West Bay efforts. If you are looking for optimal environmental impact, I’d urge you to follow the West Bay work.”

The logic is that by going after the least damaged places we have more when we finish, the low hanging fruit more bang for your buck argument. In reality, if we think of damage as a continuum, starting lower on the scale offers greater room for improvement. This concept lies at the base of Federal Law.

The City is focusing on a 120 year old railroad berm (visible on the left side of the first areal photo on page one). The railroad berm was already used as mitigation for dredging and filling East Bay. It was used as a balancing act for the Smyth Landing development at the mouth of Schneider Creek and now is now being used as a diversion from East Bay development. How many times does the City think they can use this one spot for mitigation banking?

We’re told that modifications to the railroad berm will give us the best results because it’s already regarded as the best habitat in the bay? The questions surround how much of the berm to remove, that is to say, how much mature intertidal habitat to destroy. Features like this, coastal lagoons and dendritic channels, are important natural features in river estuaries. Leveling the berm will reduce the length of intertidal shoreline, the area of salt marsh and it will destroy a benthic community that has been maturing for a hundred years. The City of Olympia is relying mainly on the West Bay Environmental Restoration Assessment Final Report of February 2016 which was created by Coast & Harbor Engineering in association with two other engineering firms. It’s an engineering report. Alternatives the City is debating, at considerable cost, will not only not be an improvement, they will likely degrade oceanographic and ecological parameters.

Over the past 40 years, the Budd Inlet ecosystem has crashed. On December 22, 1979 Budd inlet, a census taken by Black Hills Audubon members of the port area (east and west bay) totaled 3670 individuals of 35 species of waterbirds. East Bay was still full of life. “Waterbirds are represented by a diversity of species and are numerous throughout the winter months. The productive areas of Olympia Harbor are principally tidelands. East Bay and West Bay tidelands are frequented by bottom feeding birds. East Bay serves as a refuge for waterbirds during winter storms”. Other concerns are wintering, feeding, and sheltered resting habitat.

Species of benthic organisms and fish in East Bay included: Ghost shrimp (Callianassa californiensis), mud shrimp (Upogebia pugettensis), and the tube-building amphipod (Corophium sp.) were found to be abundant and widely distributed. The mud shrimp, in particular, was found only in East Bay. In Budd Inlet perch, flounder, mussels, clams, shore crabs, amphipodes, worms and barnacles were all abundant.

(The above are contained in the EIS for East Bay Marina pages: H-82, 2-4, 51,52,and F-27 through F-31 which can be found at: //apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a097636.pdf

Twenty years later the number of birds had declined. According to the exhaustive R. W. Morse West Bay Habitat Assessment, as of 2002 there would have still been daily observations of hundreds of waterbirds on the western side of the Port Peninsula, some species seasonally and some year-round. The majority of species of waterbirds had experienced “a dramatic decline in their numbers. These species include: Red-necked, Horned, and Western Grebes, Pelagic Cormorant, Surf Scoter, Barrow’s Goldeneye, Hooded, Common, and Red-breasted Mergansers, Ruddy Duck, Bonaparte’s and Mew and Ring-billed Gulls. Some waterbirds were even not recorded during the survey period although they were prevalent 15 years ago: White-winged and Black Scoters, American Wigeon, Canvasback, Rhinoceros Auklet, and American Coot”. “When an examination is made of comparable dates in December in 2001 versus 1986: in 1986, 812 waterbirds were counted (21 species) versus only 168 birds (16 species) in 2001”. “Thirty to eighty waterbirds were often seen between the Fourth and Fifth Avenue Bridges 15 years ago. Now, only occasionally do we see any birds in this area”.

Today, another twenty years later, we would likely see no waterbirds anywhere in the bay. If one could find a living fish one would be poorly advised to eat it. Forty years of simmering in the current regulatory caldron has transformed Budd Inlet into a jellyfish pond.

The final lap for Budd Inlet began in 1980 when the Port of Olympia decided to build a marina in East Bay. Several options were considered around Budd Inlet that would have required minimal environmental modifications. The East Bay choice involved extensive dredging and filling of neashore areas.

The East Bay EIS states on page 64: “Although marina construction may benefit certain species, the wetland fills reduce estuarine productivity through loss of habitat, algal species, benthic invertebrates,.. This is a complex impact which cannot be easily estimated quantitatively; however, some reduction in populations of birds, fish, shellfish, and other faunal species may be expected to occur. Such reduction cannot be accurately quantified”.

A long statement by USFWS dated July 18, 1979 on pages F-1 through F-21 conveys many simialar concerns. In a letter dated Feb 26, 1980 the USFWS wrote: “In summary, the East Bay tideflats and aquatic areas provide important habitats for high numbers of waterfowl and other waterbirds and to a lesser degree for marine fishes. Construction of the proposed project with cargo storage area would cause an excessive loss of these habitats and resources. Those losses could be significantly reduced with our previously recommended alternative eliminating the cargo storage area and non water-dependent commercial uses and employing open water disposal of any excess dredge materials. Studies and reports of the Corps of Engineers indicate such an alternative would have less adverse environmental impact and also have approximately the same benefit to cost ratio as the proposed project. As stated in a letter of September 7, 1978 to your office, the Fish and Wildlife Service supports the concept of a marina in East Bay, provided that persistent water quality problems would not result and that landfilling can be limited to the extent actually required for physical support of the marina. However, the Service can not support any plan which worsens present water conditions or does not comply with State and Federal water quality laws or criteria. Information supplied in Corps reports indicate presently poor water conditions will persist even after the construction of the new secondary sewage treatment plant scheduled to begin operation in 1983. It is our contention that the proposed project is not in compliance with Executive Order 11990 since all practicable measures to minimize wetland losses would not be taken. Elimination of the cargo fill area is practicable and would reduce losses by 50 percent. information recently received from tie Washington Department of Fisheries indicates their firm belief that significant numbers of chinook salmon released from the Percival Cove salmon rearing facility, and possibly large schools of herring and smelt, will be attracted into the marina with the likelihood of increased fish kills due to anticipated dissolved oxygen sags. This presumably would occur under any marina design which entails dredging of East Bay proper. In view of this, we recommend the permit for the project, as proposed, be denied. (page G48)

Concerning water quality, in a letter dated Feb 28, 1980 the EPA wrote: The project “may not be environmentally acceptable due to the potential adverse consequences for water quality and aquatic resources. Our evaluation of the modeling studies for the proposed marina indicates that any marina development within East Bay proper will reduce the water exchange in the Bay. The consequent increase in flushing times for the East Bay basin would probably result in extremely poor water quality conditions. (page H-46 to page H-51)

The EPA wrote on august 29th 1980: “As stated in previous correspondence, our primary concern with this project has been the high potential for a reduction in water quality, particularly dissolved oxygen concentration in the marina basin. With this exception, the project is in general accordance with other environmental factors we use in evaluating marina projects. These factors include consideration for minimizing adverse impacts on wetlands, shellfish beds and fishery areas, wild’iife, and recreation areas. The results of additional water quality model studies conducted jointly by the Corps and EPA have been reviewed and, in our opinion, demonstrate a correlation between a reduction in water exchange and reduced dissolved oxygen levels. Use of an aeralion system within the marina, however, will negate anticipated reductions in dissolved oxygen. Although we continue to support Alternative 4e as a cost effective preferred alternative, selection of Alternative 4a would be acceptable to EPA if it includes a properly designed and maintained aeration system which will maintain Class B water quality standards within the marina. This is the first time we have approved of an aeration system to mitigate reduction in water quality and our approval is specific to the unique circumstances of the East Bay project. As a matter of policy EPA does not generally support the use of an aeration system as a solution to probable water quality problems in marinas, particularly when design modifications or alternative site locations with improved natural tidal exchange would eliminate the need for long-term energy requiring mitigation systems” (page G44). Plate 13 shows the design of the aeration system.

To summarize the above, Federal Agencies first recommended choosing any of the other options as a location, they then recommended denying the permit and they ultimately acquiesced on the condition that aerators be installed. The aerators are today gone. They were installed as per the agreement and then removed.

The above are also contained in the East Bay EIS: //apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a097636.pdf

These are just a few examples. The EIS is full of questions and criticisms. It’s really a testament to how the system has failed that these concerns were not given more weight. We can now say that water quality has suffered, species have become locally extinct and the concerns repeatedly expressed, particularly by Federal Agencies, were well founded.

And is the lake really that big of a problem? Coastal lagoons are natural features in some estuaries.

In some there’s a shallow sill that keeps salt water out. This is sort of what we have now with Capitol Lake. In some the sill allows the tide to flow in at high tide creating brackish water in the lagoon. The lake could be managed to do the same, sort of, by regularly opening the dam or leaving it opened.

Another changes seasonally. During summer sand migrating down the coast closes the opening. In winter rain coming downstream from land washes the sand out of the opening, opening the mouth. To mimic this the dam would be closed in the summer and opened in the winter.

Just what dam removal is going to cost is impossible to figure out, there are so many variables. The initial cost of removing the dam is estimated to be between $25 million and $350 million depending on details and who one asks. The long term funding through 2050 might come to $66,374,000.

To be a complete restoration we’d have to do something about the Deschutes Parkway, like get rid of it. We’d have to deal with nearshore armoring and fill and estuarine culverts throughout South Budd Inlet. Removing the dam may gobble every available penny. Is the dam really that big a problem? The costs and benefits of East Bay, Capitol Lake and West Bay proposed improvements should be considered together. It’s all part of the Deschutes River estuary.

Coastal lagoons are common features on the outer coast. In Santa Cruz where I grew up there are several. From a tourist flyer: “The interplay between sand moved by ocean currents and the (San Lorenzo) river creates a seasonal sandbar at the rivermouth. When we get enough runoff from the rain, high river flows come downstream and break through the sandbar, and the river drains visibly into the ocean. When the river’s flow is too little to push the sand out of the way, the sandbar disconnects the river from the ocean and creates a lagoon.” In other words, the sand dam is open in the winter and closed in the summer. A lagoon or lake at the mouth of a fresh water source is not in and of itself a bad thing.

The Puget Sound Nearshore Ecosystem Restoration Project, a coordinated effort by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW), completed a General Investigation (GI) to evaluate “problems and potential solutions to ecosystem degradation and habitat loss in Puget Sound”. Published in 2016, The Puget Sound Nearshore Study is an attempt to analyze “ecosystem processes” the “interactions among physical, chemical, and biological attributes of an ecosystem that cause change in character of the ecosystem and its components”.

“Embayments are significant landscape features that contribute to the complexity and heterogeneity of the Puget Sound shoreline”. These include barrier lagoons, “tidal inlets, largely isolated by barrier beaches and with significant inputs of freshwater from streams or upland drainage”.

“Wetlands are present in the shallows of many landforms in Puget Sound including barrier estuaries, barrier lagoons, closed marshes and lagoons, and large river deltas. Many of these wetlands have severely declined or been lost due to anthropogenic stressors (see Appendix F for information on wetland trends). Wetlands provide foraging and rearing habitat to a variety of organisms in Puget Sound. Some species use coastal wetlands year-round, and others use the habitat during their transition from freshwater to saltwater. Along the fringes of lagoons (which are typically high salinity marine water), pickleweed (Salicornia virginica) and jaumea (Jaumea canosa) typically dominate the vegetation communities. Where freshwater is present, as in barrier estuaries, closed marshes, and large river deltas, three types of vegetated wetland classes are present: estuarine mixing, oligohaline transition, and tidal freshwater. These classes transition from more saline to freshwater as one moves upstream. In the estuarine mixing and oligohaline transition wetlands, salt marsh vegetation such as saltgrasses (Distichlis spicata) and pickleweed dominate.”

Were the ecological risks and benefits evaluated?

“The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) (42 U.S.C. §4321 et seq.) commits Federal agencies to considering, documenting, and publicly disclosing the environmental effects of their actions. NEPA-required documents must provide detailed information on the proposed action and alternatives, environmental effects of the alternatives, mitigation measures, and any adverse environmental effects that cannot be avoided if the proposal is implemented. Agencies must demonstrate that decision makers have considered these factors prior to undertaking actions.”

“Executive Order 11990 entitled Protection of Wetlands, dated May 24, 1977, requires Federal agencies to avoid adversely affecting wetlands wherever possible, to minimize wetlands destruction and to preserve the values of wetlands.”

One has to also wonder, will the costs of removing the dam preclude other work restoring most of the estuary which lies outside the dam in East and West Bay? The ongoing costs to local taxpayers of Thurston County, the cities of Tumwater, Olympia, LOTT and the Port of Olympia are predicted to also be significant.

The Washington State Department of Enterprise Services (DES) is asking these local governments to sign an Interlocal Agreement (ILA) that financially binds the taxpayers for millions of dollars annually over 24 years. Little public outreach has occurred regarding the costs to the taxpayer.

The long term funding mechanism for ongoing dredging and maintenance, if we want to maintain business as usual at the Port, will be paid by Washington State, Thurston County, City of Tumwater, City of Olympia, Port of Olympia, and LOTT in the binding ILA at a cost of $66,374,000 (includes a 4.5% per year escalation rate). Under the ILA each was assigned a percentage. Olympia 23.1% or $11,508,000 and the others 15.4% or $7,673,000 through 2050. Each jurisdiction will extract funds from different sources within their organizations. Some taxpayers would be double or triple taxed (e.g., everyone pays Port of Olympia taxes, we all live in Thurston County or one of the cities and some are LOTT fee payers).

Natural marine ecosystems are productive, resilient and maintenance free. Odds are the lake will ultimately lose the debate. But what we’ll end up with remains in doubt. So many questions remain. Aren’t Federal laws supposed to prevail? Aren’t these decisions supposed to employ the best available science?